The full list of our publications is available here.

Overview of our Research

We engage in theoretical research on various topics in the condensed matter physics of quantum matter, ranging from strongly-correlated electronic systems, quantum magnetism, topological phases of matter, non-Fermi liquids and low-dimensional systems. One of our primary goals is to understand the fascinating and complex phenomenology displayed by many materials studied in the laboratory. But this is no simple task: we seek to understand the quantum physics of a macroscopic number of electrons that are interacting with one another. And their physics appears to lie in a regime where the electronic potential energy (due to electron repulsion) is of the same order as their kinetic energy. In keeping with this, our work has often involved the development of non-perturbative methods (e.g., a novel renormalisation group method based purely on many-particle unitary transformations) and applying them towards understanding some challenging open questions and problems (e.g., the origin of high-temperature superconductivity from electrons that face strongly repulsive interactions).

Show More

Condensed matter physics involves the study of emergent phenomena in quantum matter (thats what the acronym EPQM stands for). This refers to states of matter that are obtained in systems with a large number of constituents that obey the rules of the quantum world and are interacting with one another, within certain scales (energy, length, momentum etc.) and in particular circumstances.

Superconductivity is an excellent example: when a system of interacting electrons in a metal are cooled sufficiently, they form (typically loosely bound) pairs (called Cooper pairs) and condense into a ground state that is protected by an energy gap. This ground state shows the phenomenon of superconductivity: the flow of a charge current without any resistance. In most commonly available superconductors, the formation of the Cooper pairs needs lattice vibrations that mediate an effective attraction between the electrons (and to overcome the screened Coulomb repulsion that they experience otherwise).

Emergent phenomena are usually not easy to anticipate, and appear when the interacting system undergoes a phase transition of some kind. Understanding the physics of the thermal or quantum fluctuations that drive the phase transition typically holds the key towards understanding the ordered nature of the emergent ground state. The onset of order is quantified through an order parameter. Very often, the order parameter is governed by the symmetries enjoyed by the system, as well as its spatial dimensionality. Emergent orders described by the Ginzburg-Landau-Wilson paradigm arise from the spontaneous breaking of symmetries as external conditions are changed (consider how ferromagnetism arises below the Curie temperature).

The order parameters describing the ordered state are experimental measurables (e.g., the local magnetisation, which is equivalent to the global magnetisation per particle or site due to translation invariance). The phase transition from the disordered state (with vanishing order parameter) to the ordered state (with non-zero order parameter) manifests in a singular behaviour in some quantity that can be obtained from the free energy. For instance, a first order (or discontinuous) transition is obtained in the form of a jump in the order parameter, i.e., the first derivative of the free energy with respect to temperature or a field.

Continuous transitions show up as divergences in the second derivative (i.e., a response function) onwards, possess scale invariance (in the form of a diverging correlation length) with critical thermal fluctuations existing at all lengthscales. The divergences of various quantities display power-laws whose exponents are universal, and show scaling behaviour in the reduced temperature (i.e. (T-Tc/Tc), where T is the temperature of the system, and Tc is the critical temperature at which it undergoes the phase transition). Quantum fluctuations play the same role at a quantum phase transition tuned by some parameter other than the temperature, but with scaling in both space and time.

More recently, a lot of attention has been given to how transitions can involve the emergence of states where no symmetries of the system are broken. The order parameter here could correspond to a topological property of the system (e.g., the way the wavefunctions of the system wind around the momentum-space Brillouin zone, a degeneracy of the ground state that is manifested upon changing the boundary conditions of the system etc.). A lot remains to be learnt about these states, and how they are obtained.

Very generally, understanding the emergent ordered states of a system of interacting quantum matter (e.g., electrons or quantum spins) is a very hard problem. The same is true for the phase transitions that lead to them. The physics of an Avogradro number of quantum constituents that are interacting with one another very often lies in a regime where the electronic potential energy (e.g., due to electron repulsion) is of the same order as their kinetic energy. Strongly interacting quantum matter possesses quantum fluctuations that lead to enhanced many-particle entanglement among the constituents of the system, in contrast to the poorly entangled forms of emergent matter arising from spontaneous symmetry breaking.

All of this means that approaches that rely on perturbation theory or mean-field theory often do not work when dealing with strongly interacting quantum matter (especially fermions and quantum spins!), and non-perturbative approaches are called for. This is where EPQM’s work often lies. Much of our effort has involved the creation of a new language (i.e., new tools and techniques) for fermionic criticality. Also, testing how well this new language describes experimentally observed phenomena, as this could well hold the key to the discovery of novel quantum materials (think room temperature superconductivity!) and the development of quantum devices and technology (think quantum circuitry and quantum computers!).

Show Less

Broad areas of research

We focus on the following areas in our research:

- Strongly correlated electron systems,

- Frustrated quantum magnetism,

- Non-Fermi liquids,

- Unconventional superconductivity,

- Topological states of matter and Topological order,

- Fermionic Criticality,

- Many-particle entanglement,

- Low-dimensional quantum systems,

- Quantum transport,

- Search for quantum materials

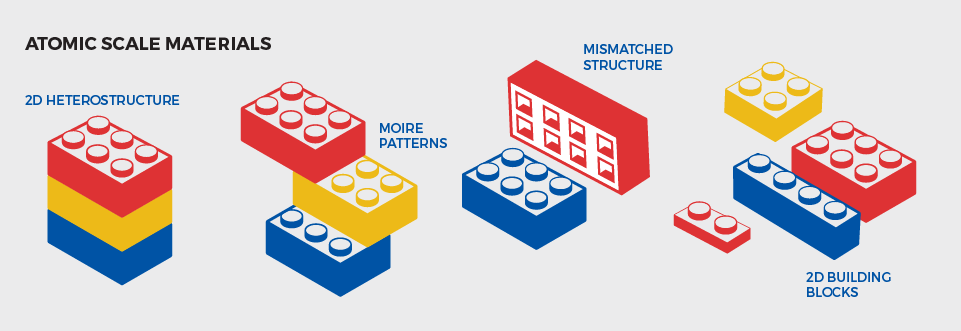

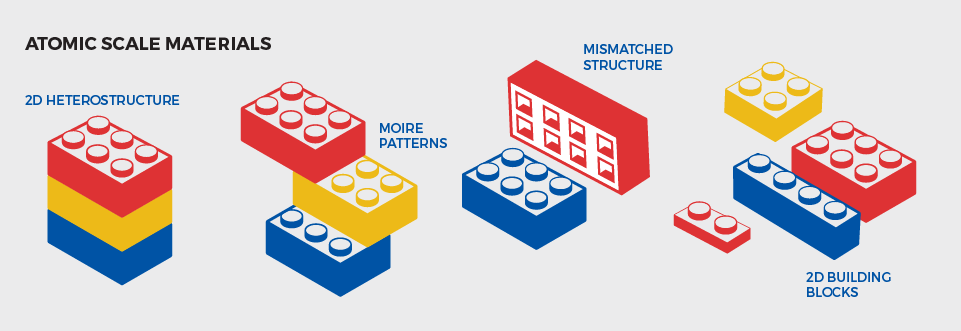

See full image.

See full image.

Methods we use (and develop)

We employ, as well as develop, analytic and numerical methods to find answers to our questions. This includes

- Variety of renormalisation group (RG) methods to determine quantum phase diagrams (critical, saddle and stable fixed points). We have developed a non-perturbative RG scheme based purely on many-particle unitary transformations that leads to stable fixed points for the evolution of the Hamiltonian and its couplings.

- We have also extended this to obtain the RG evolution of the many-particle entanglement content of the ground state, and low-lying excited states, of interacting fermionic matter.

- Methods by which to identify the appropriate quantum order parameters for topological states of matter. These are composite objects (e.g., Wilson loops) that lead to quantum ordered ground states. They are represented by operators that exploit emergent symmetries and lead to topological quantum dynamics.

Show More

- Spectral flow-based criteria in determining the existence of a spectral gap.

- Employ ideas from graph theory, algebraic topology, number theory, quantum information theory, non-linear dynamics, machine learning etc. creatively to our advantage.

- Probe topological features of sum rules that govern spectral weight transfer (e.g., Luttinger’s count of the Fermi volume, Friedel sum rule)

Show Less

Questions we have worked on

Strong correlations and exotic superconductivity

Strongly correlated systems often show the proximity of unconventional superconductivity, non-Fermi liquids and insulating magnetic states of quantum matter. Well known examples include the cuprates and heavy fermion systems. We are interested in understanding how the enhanced quantum fluctuations in low-dimensional (e.g., two dimensional) versions of such systems can enhance the emergence of complexity.

Show More

- Can a system of repulsively interacting electrons give rise to superconductivity upon tuning some parameters (e.g., hole doping, pressure etc.)?

- Can doping the ½-filled 2D Hubbard model explain the complexity observed in the cuprate high-TC superconductors’ phase diagram?

- Does the Pseudogap phase collapse towards a QCP within the SC dome?

- Can attractive interactions between electrons lead to a insulating state of Cooper pairs (instead of the broken symmetry that leads to superconductivity)?

- Can we understand the nature and properties of metals beyond the paradigm of the Landau Fermi liquid?

- Can we formulate a language for the exploration of non-local (or topological) ordering of matter?

‘The discovery of high-temperature superconductivity in the copper oxides in 1986 triggered a huge amount of innovative scientific inquiry. Unresolved issues include the astonishing complexity of the phase diagram, …, the ‘normal’ state at elevated temperatures.’[Source]

Show Less

Relevant works

Topological phases, symmetry breaking and entanglement

Topological states of matter are known to be governed by rules that depart from the traditional Ginzburg-Landau-Wilson paradigm of local order parameters and spontaneous symmetry breaking. The entanglement properties of the many-body Hilbert space are believed to be key to the ongoing search for topological order in quantum matter. We are presently focussed on asking how topological order can arise in correlated fermionic quantum matter.

Show More

- Can we formulate a language for the exploration of non-local (or topological) ordering of matter?

- How does many-particle entanglement lead to the creation of the novel gauge degrees of freedom that are found in topological quantum field theoretic approaches to some quantum liquids?

- Can the multi-particle entanglement of topologically ordered states of quantum matter be understood using measures of quantum information?

- Can we build a systematic understanding of many-particle entanglement that can help classify the “universality classes” of quantum matter?

- Where did these quantum fluctuations come from? Could they have existed in momentum-space in a UV theory of interacting electrons?

- Is something universal about such quantum fluctuations?

- How does this relate to the idea of holographic entanglement renormalization for gapless states?

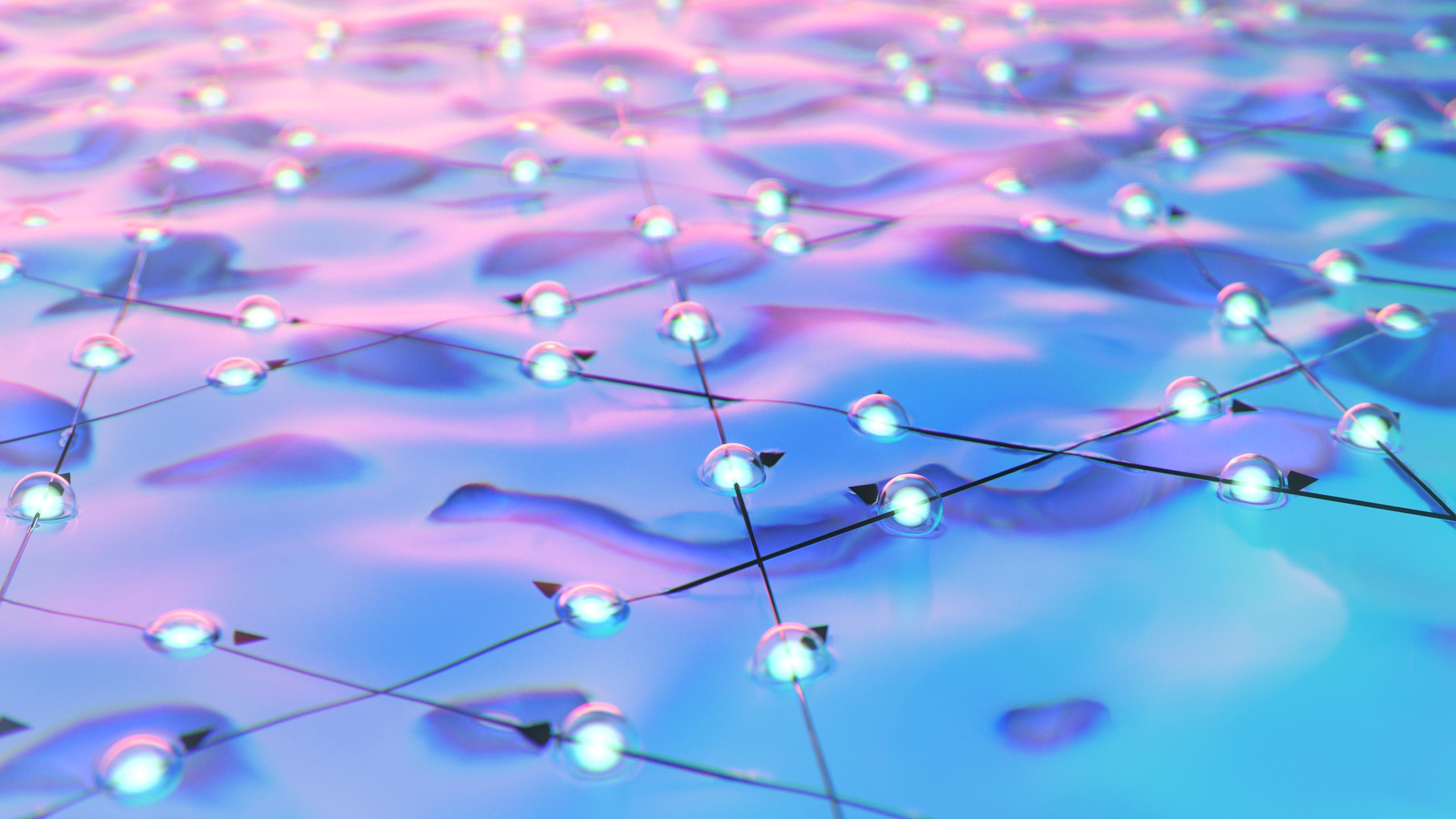

‘In entanglement, the properties of two particles are intertwined even if they are separated by great distances from each other.’ [Source]

‘In entanglement, the properties of two particles are intertwined even if they are separated by great distances from each other.’ [Source]

Show Less

Relevant works

Quantum criticality associated with correlated electrons likely require order parameters that describe the geometry and topology of the Fermi surface. We are interested in investigating quantum phase transitions that involve drastic changes in the exchange statistics of excitations lying above the ground state and changes in the topology of the Fermi surface (Lifshitz transitions).

Show More

- How does Fermi surface topology shape the criticality of a system of interacting fermions?

- Can answers be learnt in (relatively) simple models such as the Hubbard model?

- What insights can be gathered on these questions by lowering the spatial dimensionality of the system of interacting electrons (i.e., with a reduced Fermi surface, and enhanced quantum fluctuations)?

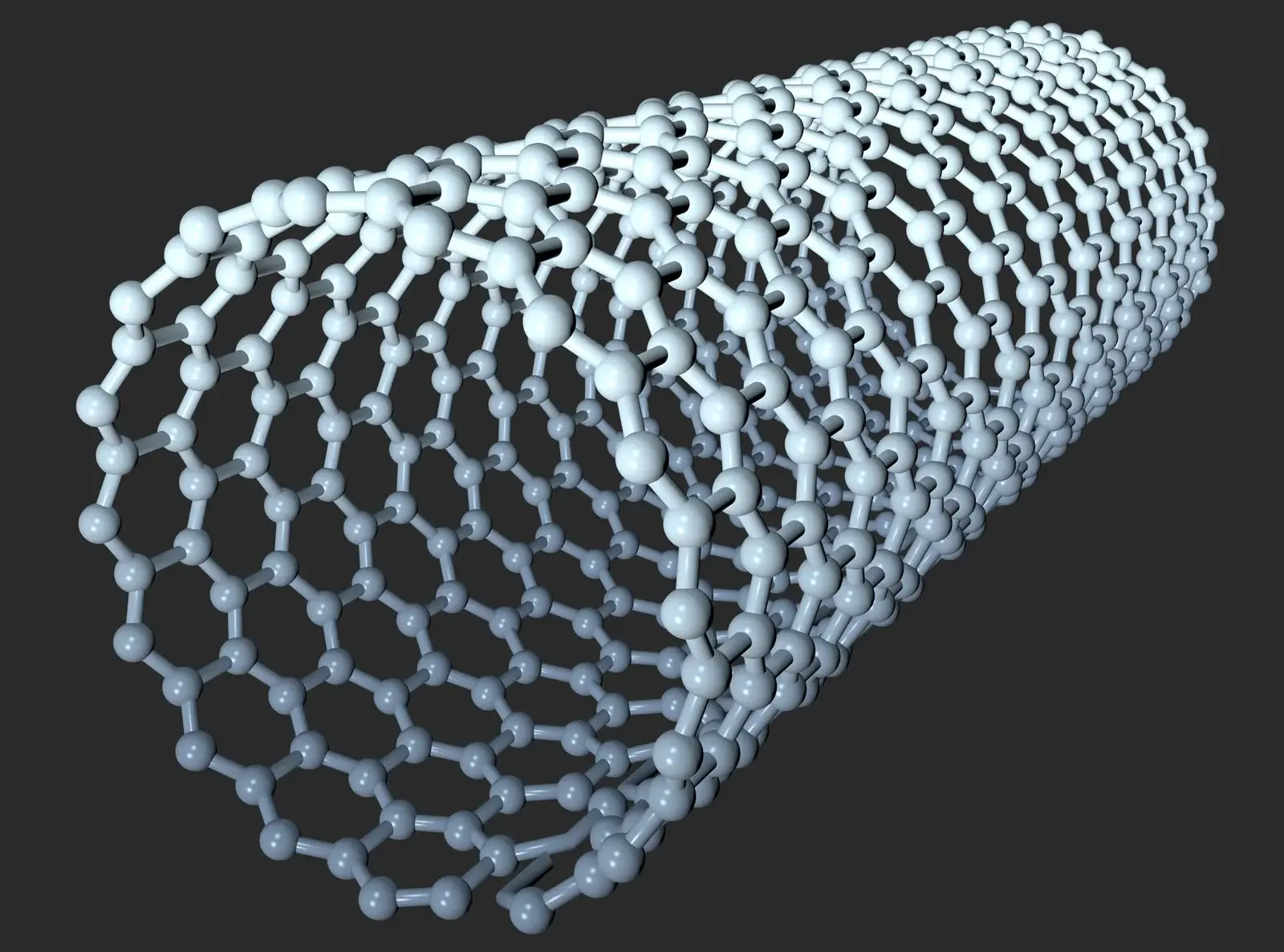

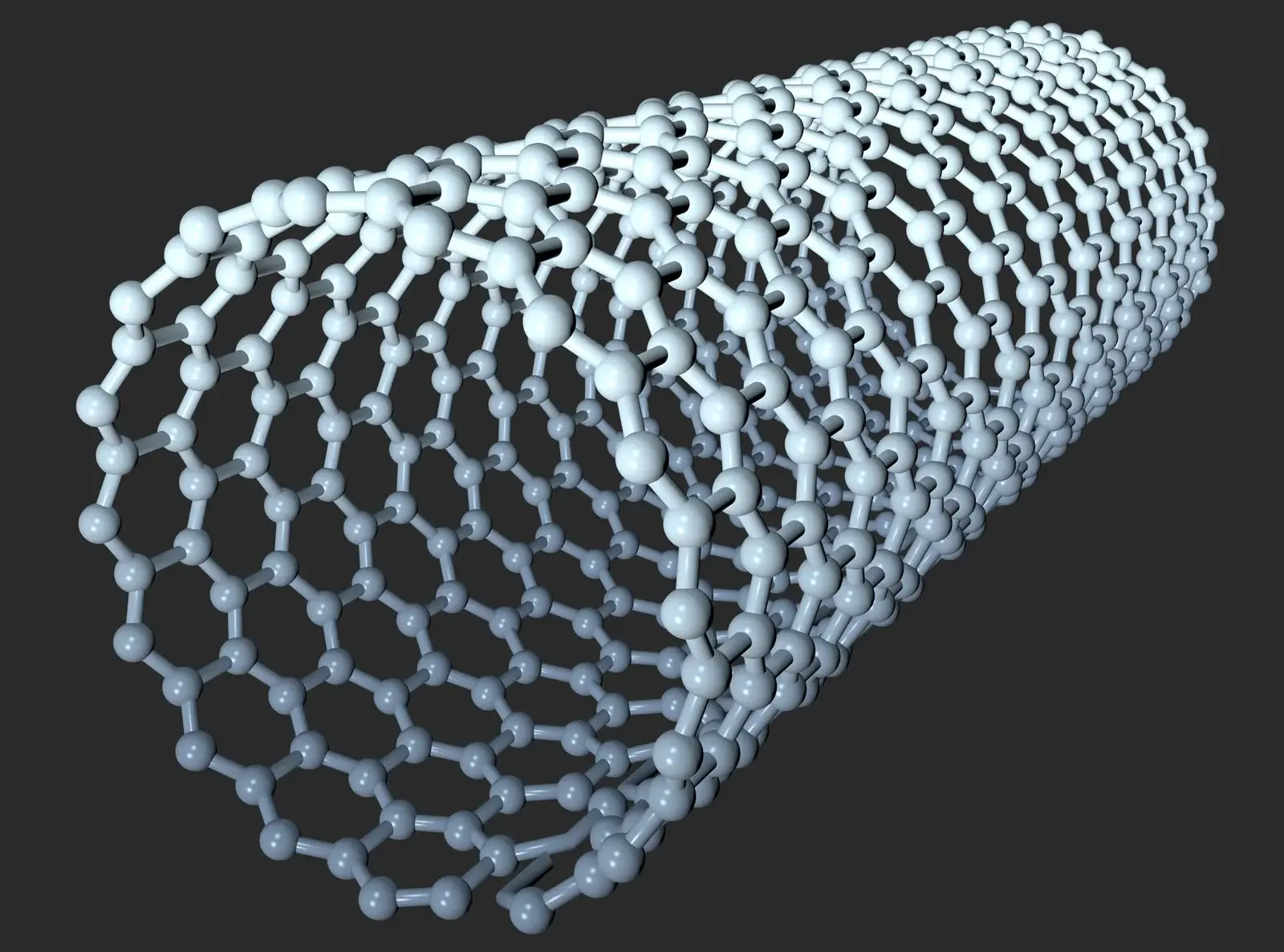

Carbon nanotubes are one-dimensional structures with special properties, rendering them with unlimited potential in nanotechnology-associated applications. [Source]

Carbon nanotubes are one-dimensional structures with special properties, rendering them with unlimited potential in nanotechnology-associated applications. [Source]

Show Less

Relevant works

Fustrated magnetism and spin liquids

The study of frustrated magnetism is at the heart of the search for liquid-like states arising in systems of interacting quantum spins. Such states do not display any ordering of the constituent spins even at T=0. Instead, there exist predictions of topological order in some gapped spin liquid states. We are interested in investigating whether such proposals can be realised in geometrically frustrated systems like the Kagome or pyrochlore lattices.

Show More

- Can frustrating interactions in a system of quantum spins lead to novel ground states that do not show local magnetic order (spin liquids)?

- Is it possible to stabilise the orbital & spin liquid states in insulating transition metal compounds?

- Using non-perturbative T=0 analytic methods, can we characterise the m=1/3 magnetisation plateaux in the kagome XXZ antiferromagnet?

- Can we extend the LSM and OYA theorems to the triangular lattice, the kagome lattice in 2D and the pyrochlore lattice in 3D?

‘A quantum spin liquid can form when atoms are placed in a triangle-like Kagome lattice. These are like the familiar phases .. but with more exotic and complicated configurations enabled by throwing superposition and entanglement into the mix.’ [Source]

‘A quantum spin liquid can form when atoms are placed in a triangle-like Kagome lattice. These are like the familiar phases .. but with more exotic and complicated configurations enabled by throwing superposition and entanglement into the mix.’ [Source]

Show Less

Relevant works

Quantum impurities & auxiliary models

Correlated quantum impurity models serve as fertile grounds for the emergence of various quantum-mechanical properties like entanglement, frustration, non-Fermi liquid physics and quantum phase transitions. They also find use as auxiliary models in methods like dynamical mean-field theory. The rich physics in these models often means that different methods lead to new insights on already-solved problems.

Show More

- What is the physics of the Kondo cloud (by which quantum impurities are screened by conduction baths in, e.g., the Kondo problem)?

- Why does the Kondo screening breakdown in the multichannel problem?

- Is there a minimal version of the single impurity Anderson model that displays a metal-insulator transition?

- What does it teach us about the MIT in higher dimensional strongly correlated electron systems?

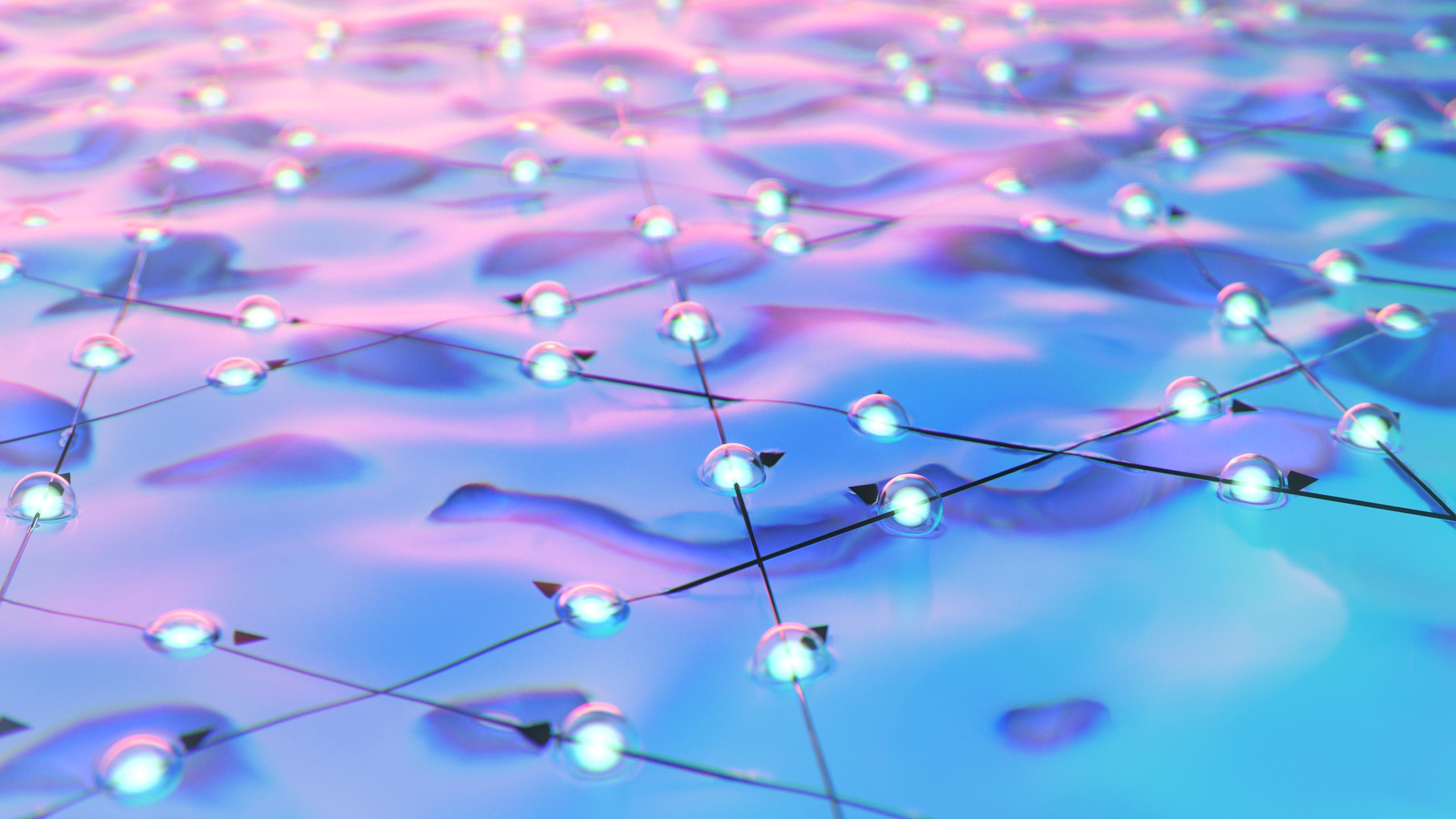

‘To model the Kondo effect, a QD is connected by means of quantum tunnelling to two electron reservoirs through electrodes that form electron-transport channels.’ [Source]

‘To model the Kondo effect, a QD is connected by means of quantum tunnelling to two electron reservoirs through electrodes that form electron-transport channels.’ [Source]

Show Less

Relevant works

Many-particle entanglement & holography

In the last few decades, quantum entanglement has become very important for studying the nature of quantum condensed matter systems. For instance, gapped interacting many-body systems typically display an area-law scaling of the subsystem entanglement entropy with subsystem size, while quantum critical systems are expected to display a volume law scaling of the same.

Show More

Further, a subdominant topological term in the entanglement entropy quantifies the long-ranged nature of correlations in topologically ordered insulating states of matter. Much less is known on the entanglement features of gapless metallic systems. Further, the holographic principle posits that the renormalisation group evolution of the many-particle entanglement of an interacting quantum field theory can be visualised as the emergence of an emergent spatial dimension.

- Can various states of quantum matter (metals, insulators, superconductors and superfluids, topological phases, quantum critical states etc.) be characterised and classified by their many-particle entanglement?

- Can topological entanglement entropy (TEE) of a topologically ordered ground state in 2 spatial dimensions can be detected via multi-particle information (MPI) and quantum correlation measures?

- Can a first principles calculation of entanglement renormalisation in a relatively simple system demonstrate the holographic emergence of a spatial geometry?

- How do the field theoretic parameters (e.g., the RG beta function) relate to the geometry quantifiers (e.g., distances and curvature) in this emergence dimension?

- Spectral flow operations on metallic systems lead to a flux-dependent piece in the entanglement entropy. Is this term topological in nature?

- If so, is there a correspondence between the topological terms in metallic systems and those obtained in the above-mentioned insulating systems?

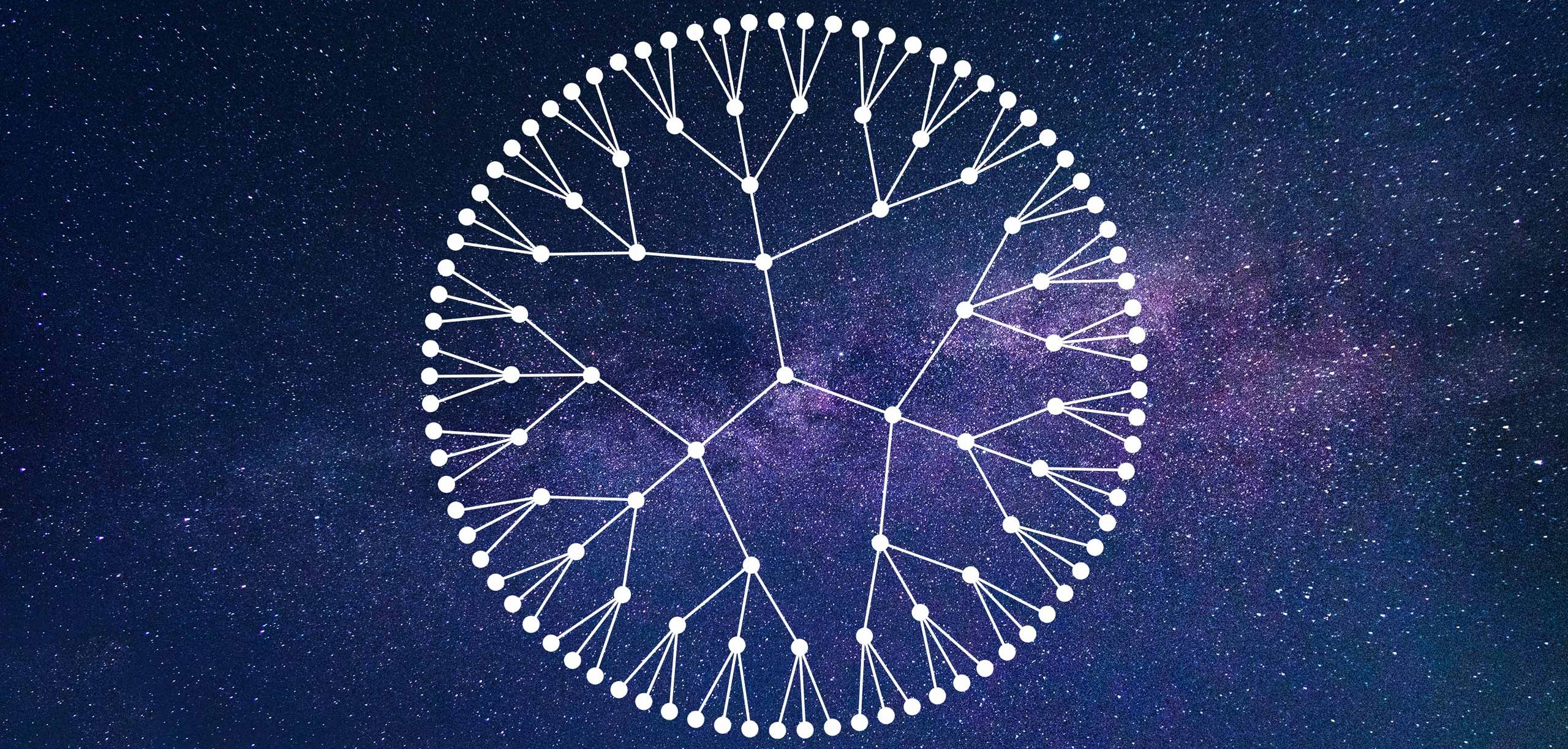

‘Quantum particles entangled in a “tree-like” structure correspond to various configurations of space-time.’[Source]

‘Quantum particles entangled in a “tree-like” structure correspond to various configurations of space-time.’[Source]

Show Less

Relevant works

Quantum transport

While transport in quantum systems is a vast field in itself, we are keenly interested in understanding how it is shaped by inter-particle interactions, low-dimensionality and the geometry & topology of the system. Systems of interest include transport on the edge states of 2D topological insulators (e.g., quantum Hall systems, graphene), quantum wires of interacting electrons (described by the 1D Tomonaga-Luttinger liquid), quantum dots of various kinds etc.

Show More

Very often, our questions are shaped by state-of-the-art experiments.

- How do the Andreev bound states induced in a graphene quantum dot by the proximity effect affect the electronic transport through it?

- Can one find a universal theory for transport in fractional quantum Hall systems with constrictions that dractically affect the filling factor in their neighbourhood?

- How does a junction linking several interacting quantum wires affect the transport?

- How is electron transport affected to the connections of an interacting quantum wire to its reservoirs?

- Is it possible to simulate the transport in a multichannel Kondo problem in a cold atomic system?

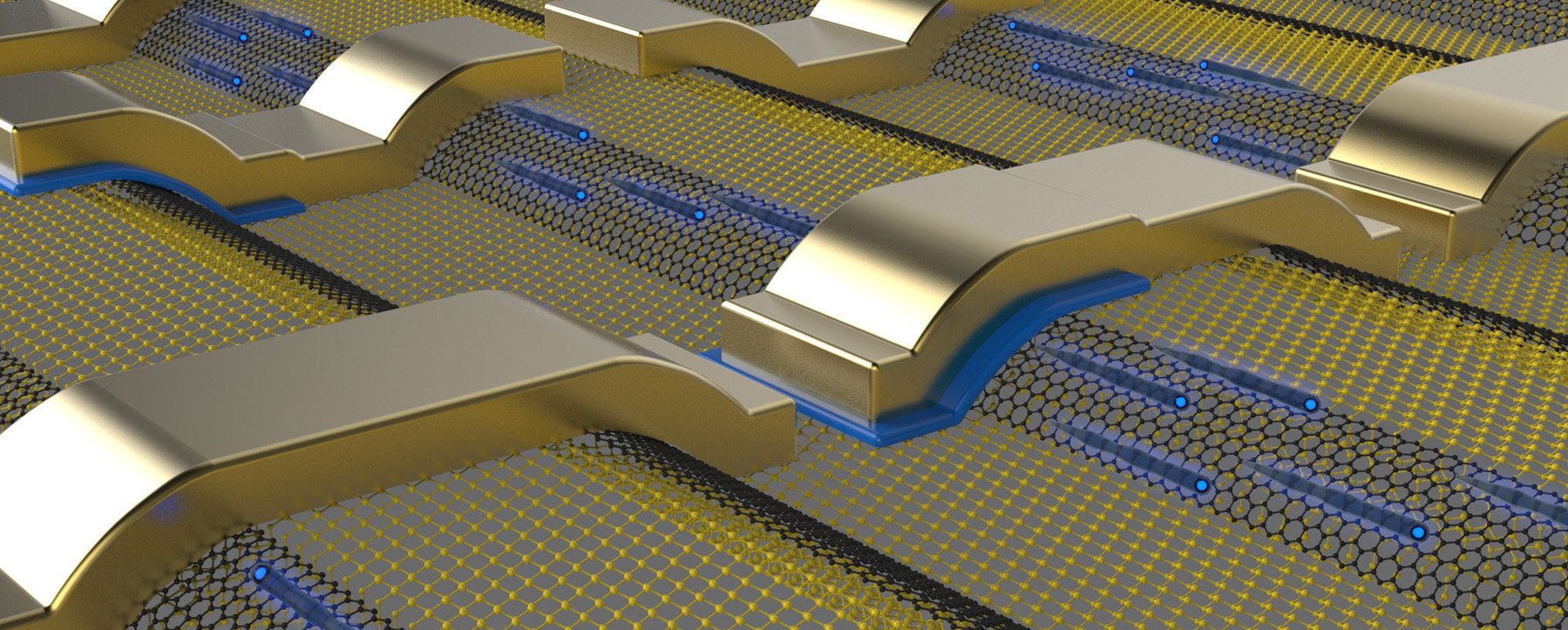

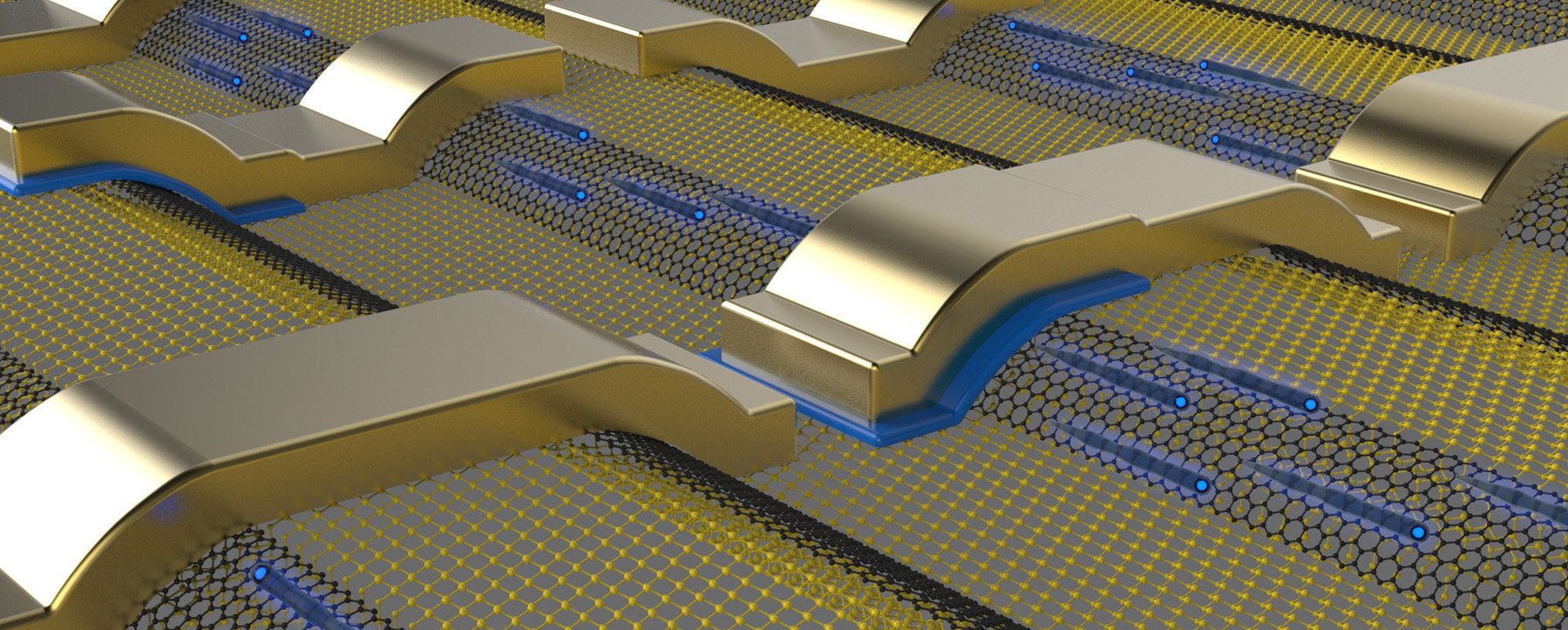

‘Conceptual drawing of an electronic circuit comprised of interconnected graphene nanoribbons (black atoms) that are epitaxially grown on steps etched in silicon carbide (yellow atoms). Electrons (blue) travel ballistically along the ribbon and then from one ribbon to the next via the metal contacts.’[Source]

‘Conceptual drawing of an electronic circuit comprised of interconnected graphene nanoribbons (black atoms) that are epitaxially grown on steps etched in silicon carbide (yellow atoms). Electrons (blue) travel ballistically along the ribbon and then from one ribbon to the next via the metal contacts.’[Source]

Show Less

Quantum materials

There are many surprises thrown up by experiments on strongly interacting quantum matter. For instance, the cuprate family of Mott insulators turn superconducting upon doping with holes. Indeed, many such puzzling observations abound in several families of materials. Over the years, EPQM has studied many of them, including the cuprates, organic conductors, perovskites, halides, spinels, insulators with active magnetic moments and orbitals degrees of freedom, materials that are effectively low-dimensional spin systems.

Show More

Questions of interest involve the nature of various phases shown by these materials, as well as the transitions (e.g., metal-insulator etc.) that lead to them. Many of these materials are of vital importance for the design of future quantum technologies, and also in the search for novel quantum materials with exotic functional properties.

[Source]

[Source]

Show Less

For more information, please visit the about page and the publications page.

Some of our Codes are open-source

Some of the numerical implementations of our methods, e.g., the unitary Renormalisation Group (URG) and the momentum-space entanglement renormalisation group (MERG) are available on GitHub and Zenodo. Please do share your feedback with us if you use/modify our codes.

Thanks to our Funders

We are thankful for research funding from SERB and IISER Kolkata for implementing our projects. Also, to CSIR and IISER Kolkata for the research fellowships for several of EPQM’s research scholars. None of this would have been possible but for the honest taxpayers of the Republic of India.

‘In entanglement, the properties of two particles are intertwined even if they are separated by great distances from each other.’

‘In entanglement, the properties of two particles are intertwined even if they are separated by great distances from each other.’  Carbon nanotubes are one-dimensional structures with special properties, rendering them with unlimited potential in nanotechnology-associated applications.

Carbon nanotubes are one-dimensional structures with special properties, rendering them with unlimited potential in nanotechnology-associated applications.  ‘A quantum spin liquid can form when atoms are placed in a triangle-like Kagome lattice. These are like the familiar phases .. but with more exotic and complicated configurations enabled by throwing superposition and entanglement into the mix.’

‘A quantum spin liquid can form when atoms are placed in a triangle-like Kagome lattice. These are like the familiar phases .. but with more exotic and complicated configurations enabled by throwing superposition and entanglement into the mix.’  ‘To model the Kondo effect, a QD is connected by means of quantum tunnelling to two electron reservoirs through electrodes that form electron-transport channels.’

‘To model the Kondo effect, a QD is connected by means of quantum tunnelling to two electron reservoirs through electrodes that form electron-transport channels.’  ‘Quantum particles entangled in a “tree-like” structure correspond to various configurations of space-time.’

‘Quantum particles entangled in a “tree-like” structure correspond to various configurations of space-time.’ ‘Conceptual drawing of an electronic circuit comprised of interconnected graphene nanoribbons (black atoms) that are epitaxially grown on steps etched in silicon carbide (yellow atoms). Electrons (blue) travel ballistically along the ribbon and then from one ribbon to the next via the metal contacts.’

‘Conceptual drawing of an electronic circuit comprised of interconnected graphene nanoribbons (black atoms) that are epitaxially grown on steps etched in silicon carbide (yellow atoms). Electrons (blue) travel ballistically along the ribbon and then from one ribbon to the next via the metal contacts.’